|

Robin Hood: King of Sherwood An extract from the novel by I.A.

Watson  I

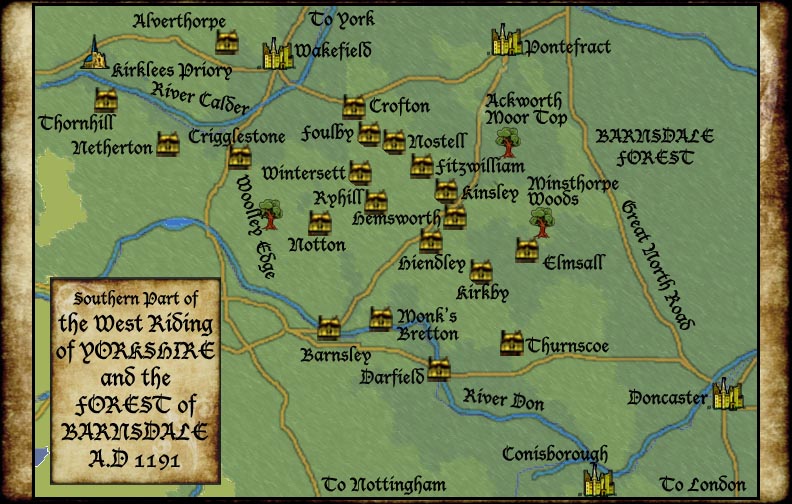

There

were outlaws in Sherwood Forest. Everyone

knew it. The thick woodland was home to masterless men and runaway serfs and

those who’d fled wild when their villages had been cleared to make the lords’

hunting parks. They preyed on passing travellers, on the forest hamlets, and on

each other. That

was why rich caravans moved through Sherwood with caution. Outriders checked

the trail ahead, ready with horns to sound alarm at the sight of bandits.

Foresters with hounds walked the flanks. Hired guards, some of them mounted,

travelled beside the carriages. The

Fitzwarren caravan was forty strong, although a score of them were only

attendants. Four of the party were women, for this group was heading on pilgrimage

to Kirklees Priory. The numbers were not uncommon for a rich train. Sometimes

the wolfsheads attacked with a hundred men. Nobody

really expected trouble. Kirklees was only half a day away and the Prioress was

expecting them. The April morning was dry and fair, the track firm, the sun

bright. It was a day for a holiday ride, not for sudden terror. Besides, while

a hundred masterless thugs might eventually overpower even a well-prepared

properly guarded caravan it would cost them half their number. Thieves were

cowards and there was easier prey to be had. The

train stopped to water the horses at the edge of a shallow river. There was a

mill there, the great wooden wheel turning lazily in the mill-race. The

outriders waited beside it, playing at dice with the miller’s son. From their

expressions they weren’t winning. The miller’s boy dared a hidden wink at the

young lady in the carriage before it moved on. “You

shouldn’t encourage them,” the older lady beside the maiden chided. “Have you

learned nothing?” The

young woman’s brows furrowed. “That boy? I did nothing, mother. I was just

admiring the view. This is lovely countryside. He decided to wink at me. I

didn’t provoke it.” Across

the carriage from mother and daughter the pair’s maids exchanged resigned

glances. Their mistresses had been bickering intermittently for three days

journey now. Lady Mary Fitzwarren was far too sensitive about attentions paid

to her youngest daughter – although maybe she had cause. The girl was too proud

and defiant to surrender to her mother’s nagging. “‘Just

looking’ was enough, Matilda. A lady in public should be demure, her eyes cast

down. You are not some common peasant chit hanging around the local inn. You’re

an heiress of Sir Richard at the Lee, daughter of a proud crusader family.” “I

know full well who and what I am, mother. You remind me of it six times an

hour.” “And

well I should. You’ll not play these tricks at Kirklees, Matilda. The Prioress

there runs a strict rule.” “Yes,

mother. That’s why I’m only bringing one wagon-full of dresses for my

stay there.” Lady

Fitzwarren didn’t catch the irony in her daughter’s voice or else she chose to

ignore it. “You’ll attend to the Prioress or I’ll have her put you on bread and

water. You’ve caused enough trouble for your poor father already. If it weren’t

for your glances we wouldn’t be in this mess we are now.” The

girl’s temper flared. “We’ve had this argument before, mother. I did nothing – nothing

– to encourage the Prince’s advances. You and father were happy enough to

parade me before him when he came to stay. You picked out my gown. You loaned

me your own jewellery. You wanted me to make an impression on him. Well

evidently I did.” Lady

Fitzwarren snorted ruefully. “That you did, Matilda Fitzwarren.” “So

what was I supposed to do?” her daughter challenged. “Lie back and think of

England? Was it my patriotic duty to let that sweaty-handed lecher pin me to my

bed? Was it?” “Of

course not, Matilda,” the older woman denied. “It’s not as if he were the King,”

she added as an afterthought. “So

what was I supposed to do when he crept into my chambers?” demanded

Matilda Fitzwarren. “I’m still waiting for a good answer to that one. Politely

ask him to leave and to please not bribe the servants again? I tried that. Cry

‘Death before dishonour’ and plunge my dagger into my breast? That would rather

spoil father’s wedding plans for me when he works out which grand alliance he

really wants. Great lords really do prefer their brides to be breathing.” “Now

you’re being silly, Matilda!” “And

you’re not answering my question again. When the second most powerful man in

England sneaks into your bedchamber demanding your virtue what exactly does

etiquette demand?” Lady

Fitzwarren didn’t really have a good answer. There wasn’t one. “Something…

something that didn’t involve stunning him with a chamberpot,” she answered at

last. “You’re lucky you didn’t get us all sent to the Tower of London.” The

ladies’ maids exchanged a surreptitious look of approval. There’d been quite a

dent in that bowl. Constanza and Aliss were impressed. The

girl was unrepentant. “Weaselly John would never admit that a woman had turned

him down. He denied it had ever happened.” “He

might deny it publicly, but he won’t forget,” Lady Fitzwarren promised. “Your father,

our whole family, will suffer for it, you mark my words. And your father will

never forgive John’s insult.” Matilda’s

cat-green eyes flashed. “First the Prince tries to ravish me then he tries to buy me!” “You

didn’t have to tell your father about John’s visit,” Lady Fitzwarren argued.

“Then he wouldn’t have had to confront the Prince – when the Prince could stand

again. And the Prince wouldn’t have offered that… that obscene bargain. And

your brother wouldn’t have challenged De Loris.” Matilda

bunched her fists. “Adam hasn’t the brains of a plank of wood!” she hissed. “I

never asked my brother to go defending my honour against the slurs of

John’s toadies.” “What

did you expect him to do?” her mother chided. “He’s a silly hotheaded fool, I

agree, but young De Loris was casting aspersions on your chastity and

character.” “De

Loris provoked a fight and he got one. Adam walked straight into it. De Loris’

only mistake was in assuming my idiot brother was as slow with his blade as he

is at thinking.” The scuffle had been more brawl than duel. The expected joust

had become an unseemly tumble in the mud. Then farce had turned to tragedy.” “It

served John’s purpose well enough,” Lady Fitzwarren said sourly. “One of his

retainers stabbed and like to die, under your father’s hospitality. Stabbed by

a son of the household. It swept away all hint of scandal about the Prince’s

behaviour. And if De Loris does not survive…” “Adam

will be charged,” Matilda sighed. The anger ebbed from her to be replaced by

gnawing frustration. The injustice of it all churned her stomach. “A

hefty fine at the least,” Lady Fitzwarren estimated. “Worse, if his highness

wants to press things for malice.” Matilda

slammed her hand down on the window-sill of the carriage. “So why, when it was

you and father who put me in Prince John’s sight, when it was Weaselly John who

crept into my bedroom, when it was Adam who put a knife into that idiot De

Loris, am I the one getting the blame for this? Why am I sent to exile in

Kirklees Priory?” “To

learn control,” her mother told her. “Self-discipline. You’re a grown woman

now, Matilda, not some wild scrubby child climbing all over the grange. Your

encounter with the Prince should have taught you that much, at least. Your

father is working to make you a good match but until then we’ll all feel much

safer with you confined behind the walls of a nunnery.” A

new thought suddenly came to the young woman. “You don’t expect Prince John to

try and… harm me, do you? I mean, he wouldn’t…” “As

you said, John is a powerful man, and you’ve hurt his pride. Your father would

protect you, of course he would, but it could put him up against an enemy too

great to withstand. It’ll take all his influence to save Adam from imprisonment

or banishment. Better if you’re out of sight and out of mind with the white

sisters,” Matilda

blinked across at Constanza and Aliss’s faces. She was missing something. A

nasty suspicion began to breed in her thoughts. “Mother… does father expect

John to demand my company to free Adam from the charges against him? Is that

the trap Adam led us into?” “Your

father knows his own counsel best, Matilda. It’s not seemly for a young woman

of breeding to harbour such nasty thoughts. God grant Kirklees will teach you

some obedience and some peace. God grant it keeps you safe.” Matilda

caught her mother’s hand. “Are you saying there is some danger? But John

must behave himself. Any scandal and the King will delight to humiliate him

with it and devise some punishment. It’s not too long since John and Richard

fought to inherit the crown and there’s no love lost between them[1].” Lady

Fitzwarren’s face changed. “Matilda, Richard sails from Dover today. The King

has answered the Pope’s call to crusade and has taken the cross.[2]” Matilda

couldn’t believe it. “King Richard is gone?” “What

do you think all those extra taxes were about?” her mother challenged. “Your

father had to squeeze the peasants hard just to make the scutage[3]

in lieu of going back to Jerusalem with the king.” “And

you didn’t think to mention any of this to me until now? Who is royal steward

until Richard returns?” Her mother’s face betrayed the answer. “Not John! Oh,

come, mother, Richard wouldn’t do that.” “No, but John

has his supporters, dear. There are Justiciars set in place, Lords Seneschal and Marshals and High Sheriffs

and things appointed across England but John is here and Richard’s not. How

long before he manages to grab the throne?[4]

I don’t pretend to understand all the politics of it – that’s your father’s

business – but the short of it is that Richard’s gone, John’s in charge, or soon will be, and

you’re going to Kirklees Priory.” “And

good riddance to me?” scowled Matilda. “Maybe I should have laid back and let

Weaselly John have his way. Adam would be free and I could have been installed

at Windsor by now.” “Matilda!”

snapped Lady Fitzwarren, shocked. “Not

really, mother,” the girl snorted. “I couldn’t bear it, those spidery hands all

over me. Ugh! Just the thought of it…” Constanza,

Matilda’s lady-in-waiting, interrupted the exchange. “Excuse me, miladies,” the portly old nurse intervened,

“The carriage has stopped.” The

Fitzwarren women looked out of their windows and realised that the caravan had

ground to a halt. “What’s going on?” Lady Fitzwarren demanded of the captain of

the guard. “What’s the delay?” “That’s

what I’m trying to find out, milady,” Loren de Weynold replied. The guard commander

seemed in a bad temper but he forced himself to speak

respectfully to his lord’s wife. “There’s a wagon shed its load on the bend up

ahead, there’s hay all over the road, and the driver is some kind of blithering

simpleton.” Matilda

craned her head out of the carriage to see. Sure enough, there was a peasant

cart on its side, one wheel still spinning. The wain had managed to catch a rut

on the side of the track and bounce over. It had been piled so high that it

must have been top heavy. “Get

it cleared, then,” Lady Fitzwalter demanded. “I don’t want to have to travel at

night.” “We’ve

plenty of time, milady,” the captain assured her. “If I can just convince that

imbecile to let me unstrap his horse. Well, what he calls his horse.” Matilda

could hear the peasant’s mumbling, a thick country accent that rendered his

speech nigh-unintelligible. He lurched towards de Weynold with a pronounced

limp. “Just

get that by-the-Lady thing moved, idiot!” the captain roared at him, but the

carter waved his good arm and tried to urgently explain something in his

fumbled language. Lady

Fitzwarren’s patience had already been tested by her daughter. This was too

much. “Send that man here to me,” she demanded. “I’ll speak to him and set him

right.” “He

smells, milady,” de Weynold objected. It

was too late. The carter limped over to the carriage, spewing out words that

almost seemed to make sense, pointing animatedly at the wagon and the nag

between its traces. “I

think he’s worried that his horse will be hurt,” suggested Matilda. “Or maybe

it is hurt and he wants to help it. That horse is probably his most precious

possession.” “Now

listen here, my good man,” Lady Fitzwarren said in a loud slow voice, as if it

would help a native Anglo-Saxon speaker to follow Norman French, “We need to

move your cart so we can get on. Move – your - cart.” The

carter nodded frantically then shook his head equally frantically. He leaned

right up to the carriage till he was face to face with Lady Fitzwarren – then

flashed a dagger to her throat. “Nobody

move!” he called out. “Nobody move and the lady comes to no harm.” Matilda’s

hand darted to her sleeve where she hid her own knife. “Don’t,” the outlaw warned,

twisting the blade at her mother’s neck. He shot her a sudden grin and gestured

to the blade. “Right now, this is my most precious possession.” “You

are surrounded by fifty armed men,” Lady Fitzwarren warned him, exaggerating

for effect. “Any one of them could shoot you dead.” “But

not fast enough to guarantee I don’t cut your weasand as I die,” the bandit

replied. There was little trace of the thick accent he’d affected, and no limp.

In fact beneath the grime his face was young and regular. Loren

de Waynold froze, unsure what to do in this unexpected stand-off. He chose

caution and gestured for his soldiers to hold their places. “A

robber,” scorned Matilda Fitzwarren. She glared at the young wolfshead. “A

robber and a coward.” The

outlaw looked hurt. “Coward? I’ve just slipped in amongst fifty armed men, any

one of whom could shoot me dead. Don’t you think that’s just a little bit

brave?” “You

have a knife at my mother’s throat. I think that’s abominable.” The

outlaw had the grace to wince a little. “Well, I’m committed now,” he pointed

out. “It’s probably a bit late for an apology and you let me go. Besides, I

have seven men in the bushes. If I back down now they’re going to tell our

leader that I’m a complete failure. And Handsome Jack doesn’t like failures.” The

captain of the guard had drawn his sword but he halted his approach again as

the wolfshead threatened his lady anew. The outlaw opened the door of the

carriage so he could wrap an arm around Lady Fitzwarren to prevent her escape. Matilda

edged towards her dagger again. “Really,

don’t,” the outlaw begged her. “I don’t want to hurt this lady. You don’t want

her hurt. We have common ground. That hidden knife, that’s going to bring us to

a place neither of us wants to be. Drop it out of the carriage nice and

slowly. Please.” Matilda

glared at him. He smiled appealingly. She scowled back and dropped her dagger

out of the window. “Now,

captain,” the outlaw called, “in a moment I’m going to whistle and some

rough-looking types will come down out of the trees. You’re going to

make sure none of your men does anything heroic like shoot at them or sound a

horn or loose the dogs. You know why, so I don’t have to make horrible threats

and so on. Just let those men rummage through your baggage carts and they’ll be on

their way.” “The

things in that second cart are for Kirklees Priory!” objected Matilda. “They

eat well at Kirklees,” the outlaw replied. “We’re hungry.” “A

lot of people are hungry,” scorned the girl, “but they don’t steal.” The

outlaw whistled. Half a dozen ragged bandits slunk out of the treeline and

cautiously came down the path. “It

worked?” one of them asked. “He actually did it?” “He

did it!” a second one agreed. “And he’s not even dead.” The

thieves shouted for the soldiers to throw down their weapons and gathered the

captives together by one of the wagons. The men-at-arms and de Waynold were roped together

with professional ease. The

oldest of the bandits took charge with the confidence of long experience,

directing the others to search

saddlebags as well as the baggage carts. It became clear that the

thieves intended to take the horses. “And

how do you expect us to get to Kirklees Priory?” demanded Matilda. “You

could walk,” shrugged the outlaw holding her mother hostage. “It’s supposed to

be good for the soul. Think of it as a pilgrimage. Or a penance.” He looked

over at the girl again. “You’re not going to be a nun, are you?” he shuddered. “That’s

none of your business,” Matilda answered. “That’s between me and God.” “Well,

you shouldn’t be,” the outlaw told her. “You’re too pretty to be a nun.” “Rob

us if you must, wolfshead,” snapped Lady Fitzwalter, “but do not address my

daughter in that fashion!” “Why

not?” demanded the thief. “Who is she?” “I

am Matilda Fitzwarren,” asserted the girl, “and this is my mother, Lady Mary of Alnwick, wife of Sir

Richard Fitzwarren of Leaford and Verysdale. That’s Sir Richard at the Lee, the

former crusader, one of the king’s own thanes.” The

outlaw’s eyebrows rose. “One of the king’s own thanes,” he repeated, slightly

mockingly. “Well then, that changes everything.” “You’ll

let us go?” demanded Lady Fitzwarren. “I’ll

take you for ransom,” replied the thief. “You must be worth a shilling or two.” “You

will do no such thing!” screeched the lady. She turned her head sharply to

remonstrate with the bandit and nearly slit her own throat. “Milady,” her maid warned, “be calmed. Your heart.” Constanza

had spotted the signs because she had seen them before. Lady Fitzwarren’s face

became as pale as a ghost. She slumped back limply into the outlaw’s arms. “What’s

going on?” he demanded, nonplussed. “She’s

having a heart seizure,” Matilda told him accusingly. “Get away from her so we

can attend to her properly.” “She’s

had these before?” “Yes.

Now stand aside.” The

outlaw shook his head. “I was only pretending to be a blithering imbecile. If I take my

knife from her throat then I’m a dead man. So are all my comrades. This could

be a trick.” Matilda

glared at him as if she’d like to see him buried up to the neck beside an ant

hill. “I swear by the Holy Rood this isn’t a trick. But if you insist on a

hostage, hold your blade to me and let Constanza care for my mother.” The

outlaw quickly considered and consented. Matilda was a much prettier hostage

anyhow. He pulled her down from the carriage to give the ladies-in-waiting

room to do whatever it was they were doing to Lady Mary. It seemed to involve the loosening

of stays. Now

Matilda was pressed up against him and he couldn’t help but become aware of her

body. She was tall for a woman, with Saxon-red hair filleted in a net of seed

pearls. She was slender and graceful, even with a knife to her throat. She was

beautiful. “Don’t

get ideas,” she told him. “The last man who did got a broken head.” “I’m

not that kind of robber,” the outlaw told her. “You are safe with me.” “Says

the man with the knife to my neck.” “That’s

just business. There was no way we could take your caravan without trickery and

a hostage. You’re making a rich pilgrimage to a richer priory where the nuns

live in luxury while their tenants starve. Anything you’re carrying is fair

game.” The outlaw sighed. “You are not.” “But

you’ll hold us for ransom?” Matilda challenged. “That’s what you threatened.” The

older man directing the plunder heard their talk. “Ransom, aye,” he agreed.

“You’ll be our guests in the greenwood until your menfolk pay for your return.

It’ll be a fair old payday when they buy back you and your mother.” “Just

her, Stutely,” the younger outlaw answered. “Her mother’s ill. We can’t drag her

to the woods and camp her on the turf. She’ll be a nuisance at best and if she

dies we’ll be murderers. We’ll just take Matilda here. She’s ransom enough.” A

whole spectrum of responses flashed through Matilda’s mind: relief that her

mother was to be spared; gratitude that her captor had some sensitivity and

mercy; concern that she was to be taken hostage; worry that she was to be

carried into the wilderness at the mercy of brutal masterless men; anger that

she had no way of crippling the insolent youngster that held her. The

older lady-in-waiting looked up from reviving her mistress. “If you’re carrying

off Lady Matilda then you must also take me,” insisted Constanza. The

young outlaw glanced up at the old nurse, regarding her girth. “If we’re

carrying you away we’d need to steal one of the wagons,” he observed. “And we’d

need to loot a lot of extra provisions.” “Don’t

be rude!” snapped Matilda. “She’s only protecting me.” The

outlaw spoke quietly into her ear. “I’m only protecting her. Look, you’re a

great lady. Your father or your betrothed will pay for you to be returned

safe and unspoiled. Unless that large battleaxe attending your mother has a rich

protector she’s not as safe in a bandit camp. So I don’t want my lads getting

the idea we should take her along, right?” “Right,”

breathed Matilda, her heart beating a little faster as she realised just how

dangerous her situation was. It was dire indeed when her best protection was

the man holding a weapon to her jugular. “Constanza, mother needs you. I shall

be safe.” “Then

take Aliss,” Constanza insisted. “Aliss

is terrified,” Matilda pointed out. “Aliss is better with you. I’ll be alright.

Go to Kirklees. Send word to the Sheriff of the shire. Send word to father.

Tell him to find these bandits and hang them all high.” “Better

yet, tell him to send ransom,” Matilda’s outlaw countered. “He’ll get word of

our demands from our leader, Handsome Jack.” “Do

not fear, my lady,” the captain of the guard called out before a bandit shoved

a rag gag into his mouth, “We shall find you and see you safe.” “She’s

safe if you bring the money,” the outlaw told him. “Honestly, it’s really

simple.” He turned to the soldiers. “And speaking of simple, let me mention what’s

going to happen next. Me and my bold comrades here will take your horses and weapons

and all the best stuff from your wagons. We’re going over to those trees there

and we’re walking away. You’re not going to follow us because we’re also taking

the Lady Matilda, and if you come after us we’ll slice her throat.” The

young woman suppressed a tremble. She couldn’t let her fear show. She was only

hostage now because she’d arrogantly announced herself. Her mother had been

right in part about her being too bold. “Now

we don’t want to slice Matilda’s throat,” the thief went on. “Slitted throat

means no ransom. You don’t want us to open her gullet either. That’d upset your

lord and who’d take the blame? So the best thing is don’t follow us. We know

the forest and we’re amazing at woodcraft and we can spot a tail a mile away.

So just don’t. You look to your Lady Fitzwarren and we’ll see no harm comes to

her daughter. Unless you don’t pay. Everybody clear?” The outlaw snapped his

fingers. “Good. Then we’ll be on our way. We thank you for your assistance and

bid you all a good day.” He

assayed a formal bow to the ladies in the carriage, then dragged Matilda off

into Sherwood. The

trek was long, much further than Matilda was used to walking. By mid afternoon

she was sweating hard and seriously regretting not demanding a change of

footwear before being kidnapped. After the second hour of trudging along

poacher’s paths into the depths of the forest she broke her self-imposed

silence. “How

much further?” The

outlaw halted and grinned at her. “Because we’re going to give away our hideout

secrets to somebody who wants to see us hanged,” he suggested. The

girl scoffed. “What am I going to say? We walked past a bunch of trees, and

then a bunch of other trees, and then we turned left by some more trees? I just

want to know how far we’re to travel.” “A

fair way,” the thief admitted. “We really need to put some distance between us

and that captain of yours before we think about joining our main group. No

matter how much booty I came back with Jack wouldn’t be happy if I led the

forest wardens to his den.” Matilda

had thought of leaving behind objects that might help foresters pick up her

trail, but the main problem with that was that she hadn’t really got a lot to

drop. “So how far?” she persisted. “These slippers weren’t really designed for

forest hikes.” The

outlaw peered up at the sun through the tree canopy. “We’ll travel until

sunset,” he judged. “Then we’ll camp overnight and rejoin Handsome Jack

tomorrow.” “You

don’t have a pavilion, do you?” Matilda realised that for the first time in her

life she’d be camping outdoors, on the ground. “We

have blankets,” the outlaw replied. “Your blankets, actually. On the horses.

It’s only fair that we lend you some.” She

glared at the outlaw as he returned to his march. “What’s your name?” she

demanded. “So that we’ll know what to put on the reward posters.” “Robin Hood,” the young outlaw told her. She

hadn’t really expected a reply. “Is that your real name?” “It

is now. Robin Hood of Sherwood.” “And

you don’t mind telling me, knowing that you’ll be hunted from here to

Nottingham for carrying me off?” Robin

shrugged. “I’d like to be famous. Before I’m hanged.” Matilda

snorted. “I’ll see what I can do. About both.” The

outlaw trotted companionably beside her, not at all bothered by the threat of

capital punishment. Matilda tried ignoring him again for a while, but

eventually had to break her silence. “The

captain and the other soldiers,” she asked, “why didn’t you kill them?” “I’m

a thief, not a murderer. And too many bodies attract too much attention from

the Sheriff’s men. And I needed somebody to bear a message back to your

father.” “My

father is going to flay you alive,” Matilda pointed out. “Well,

there’s not a lot of point flaying me if I’m dead,” Robin supposed. They

walked some more. The forest was colourful with wood anemone and celandine

coming to bloom. Birds sang and squabbled in the canopy overhead. Matilda might

have enjoyed the beauty of her surroundings if not for the company. At one point the

trail dipped down to a river valley and the outlaws forded a stream on a set of

wobbly stepping stones. Aware of the smirks of the men accompanying them

Matilda distained Robin’s hand and balanced across by herself. Further on they

passed a ruined hut, long since burned. They met no-one. “Am

I really safe with you?” Matilda asked Robin suddenly. “I mean, as a maiden?” “Quite

safe,” Robin assured her. He gave her a wicked smirk. “I don’t need to force

myself on girls.” Matilda blushed.

“Can I have my knife back, then? So I feel safe.” “I’m

not sure how safe I’d feel then. Will you give your word only to use it to

defend your virtue, not to try and escape?” Matilda

hadn’t expected so positive a response to her request. “I’ll swear it by the

Virgin,” she promised. “Go

on then, swear,” Robin prompted her. When she made her vow he handed her blade

back to her. She

received the knife with a puzzled frown. “You are a very unusual outlaw,” she

admitted. “Really?”

Robin grinned again. He seemed to do that a lot, and when he smiled his whole

face lit up like a little boy getting a treat. “What kind of outlaws are you

used to, Lady Matilda?” *** *** [1] At the time of Henry II’s death in 1189 only two of his legitimate sons survived, Richard the Lionheart and his younger brother John. Richard had warred against his father and John was said to be Henry’s preferred heir, but Richard had both the political support and military capability to ensure that John’s resistance to his claims was short-lived. [2] After Saladin captured Acre and Jerusalem in 1187, new Pope Gregory VIII proclaimed a Third Crusade to recapture the Holy Land. Richard became King of England in July 1189 and remained at home only long enough to gather funds and an army to respond to the Pope's call. He left England in early 1190 and met with Philip II of France in Marseille to travel to the Crusades together. Although Richard was King of England for eleven years he spent less than half a year of that time in England. [3] Scutage, or the Knight’s Fee, was a payment made by a noble to the king instead of having to serve in a military campaign which their feudal duties would otherwise demand. [4] Actually King Richard appointed Lord Chancellor William Longchamp, the Bishop of Ely, and Hugh de Puiset, the Bishop of Durham, to run things in his absence as his Justiciars. However, Longchamp soon sidelined de Puiset and then Prince John undermined Longchamp until the Bishop of Ely was eventually forced to flee England, leaving John in control.

|

Continued in "Robin Hood: King of Sherwood"

Continued in "Robin Hood: King of Sherwood"