|

Robin

Hood: Arrow of Justice

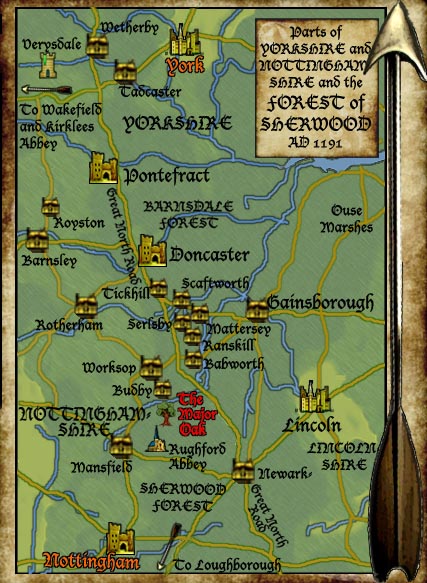

man and a boy drove their cart down the road

from Worksop to Nottingham. It was an old cart, much mended, and it moved

slowly because its creaking boards carried a heavy locked trunk. The chest was

fastened with an expensive padlock, a rarity seldom seen except to protect the

greatest of treasures. Around five miles out of Tickhill, where

the great forest pressed closest to the road, an arrow from the trees embedded

itself in the side of the wagon. A rough voice shouted “Stand!” The carter and his lad yelped and dived out

of their seats, taking shelter on the far side of the cart. A second arrow from

the other side of the road went wide and skittered along the track, but the

message was clear: the travellers were surrounded on both sides. “Don’t shoot!” the carter called, placing

his hands in the air. “I beg you, spare us!” His lad climbed right under the

cart and cowered there. The outlaws came from the forest, holding

their bows ready before them, swaggering at their victory. Their leader swung

down from a tree and landed neatly before the prisoners. “What have we here?” he wondered, looking

down at the trembling carter. “Two ragged men carrying a big sealed chest

through my forest? What’s in the box?” “P-please, sir, we don’t know,” stammered

the cringing driver. “Master, he told us to take it to Nottingham so we did.

Master’s man there, he has the key. We’re just doing what master told us!” The bandit leader looked discerningly down

at his captives. They seemed too scared to lie. “Break it open,” he called to

his men. It was a difficult job. The box was shod

with iron and the padlock was tempered steel. Eventually a dozen men, fully

half the band of wolfsheads that had waylaid the travellers, were called in to

demolish the chest. “Who are you?” the carter asked as the men

attacked his property. The bandit leader puffed his chest and

strutted. “They call me Tod Gallows, and I’m the outlaw king!” The young lad looked up curiously. He was

barely old enough to shave and his simple face looked puzzled. “King? I thought

the King of Sherwood was Robin i' th’ Hood?” Tod Gallows spat. “Hood? He’s nothing. Piss

and wind. Don’t you believe a word of him.” “They say Robin Hood killed Handsome Jack

himself,” noted the carter. “I don’t pay heed to any,” replied Gallows.

“They all fear me.” “They say Robin Hood robs from the rich and

gives the spoils to the poor,” the carter went on. “More fool him if it’s true,” spat Tod

Gallows. “I take what I want and no man tells me no.” The carter dropped down to squat beside the

lad beneath the cart. “Is that what you told that poor lass from Serlby last

week when you caught her on the road and left her for dead?” he asked; and his

tone had changed. Tod Gallows looked down at the carter.

Robin Hood looked back at him, holding the bow that Much the Miller’s Son had

passed him from its place of concealment under the cart. The string was drawn

back and a red-fletched arrow pointed right at Gallows’ throat. “You’re mad, carter,” the bandit murderer

growled. He still thought he’d found two helpless travellers and this was their

final act of defiance. “You’re outnumbered and surrounded.” The men on the cart

had seen what was happening and they stood ready to pounce. “I’m not a carter,” Robin told them. “And

I’m not outnumbered.” Much smiled happily as the villains that

surrounded him. “He’s Robin Hood,” he told them helpfully. “I’m Much.” A flight of arrows came in from both sides

of the road – but not from Gallows’ rogues. These shots were considerably

better aimed, landing between the legs of each of Gallows’ gang. “And those are my merry men,” smiled Robin

in the Hood. Gallows called to his own men in the

forest. There was no reply. “Anybody who moves now dies,” Robin advised

the bandits. “And by the way, you should always keep a watch behind you when

you take a traveller on the road. It’s a basic precaution.” Tod Gallows glared at the laughing outlaw.

“What do you want, Hood? Forest’s big enough for both of us.” Robin shook his head. “It isn’t. It stopped

being big enough the day you raped Maude of Serlby then put a knife in her

belly. That’s when you forfeited your chance to join with me and signed your

death warrant.” “Murder me, is it?” sneered Gallows. “Is

that how you did for Handsome Jack as well?” A giant emerged from the treeline, hefting

a stave as tall as himself. “Robin killed Jack in fair combat,” Little John

announced to all. “I saw it. We all did.” He stepped up to Tod Gallows and

looked down at the bandit. “Robin’s not a coward who preys on the helpless and

murders little girls. He’s not scum deserving of death.” Gallows would have backed away from the

angry giant but Robin’s arrow was still aimed at him. “There’s a code,” Gallows

remembered. “A forest code. I can challenge Hood, as Hood challenged Handsome

Jack.” Robin’s smile turned wolfish. “Yes you

can,” he agreed. “Mortal combat, one on one.” “Then I challenge you,” Gallows answered.

“It’s time for you to die.” Robin’s men exchanged smug glances that

worried the killer bandit more than any boast could. Hood lowered his bow and drew his sword.

“There’s a new forest law in Sherwood now,” he announced. “My law. Your time

has gone.” Gallows lunged forward suddenly, almost catching

Robin with the edge of his blade. Hood swerved sideways, barely avoiding.

“That’s my trouble,” Robin said as he parried the next set of blows, “always

talking too much.” He came off the defensive and began to drive his opponent

backwards round the cart. “I mean “Die!” shouted Gallows, turning again and

trying to hold his ground. “Die you bastard!” “On the other hand, at least my dialogue is

interesting,” Robin continued, retreating a little before his enemy’s fury.

“I’d like to think that I could manage a little bit better then ‘die!’ when I’m

in mortal combat. What kind of last words are ‘die, bastard’?” “Shut up!” screeched Gallows, losing all

self-control. “Shut up and die!” “Again, the dying,” Robin scorned. “How can

I come up with sparkling repartee if you’re not going to do your part? Couldn’t

you try just a little bit hard…” And then Robin in the Hood slipped in the

mud, stumbling against the side of the cart. For a second his guard was down. “Die!” Gallows shrieked and brought

his longsword about in a high arc to cleave Robin’s skull. Robin slipped aside as he’d always

intended. Gallows’ blade bit deep into the side of the wagon and lodged in the

planks. Robin swung his own sword lightly, catching

Gallows as he tried to heave his weapon free from the wood. The tip of Robin’s

blade sliced neatly across Gallows’ throat. The rogue staggered to the side

then dropped to the dirt, clutching his throat where his windpipe had been

severed. Robin was suddenly grim. “You had your

chance to speak, to surrender, to beg forgiveness for Maude of Serlby. You

wasted it. May you rot in hell.” The stricken bandit crawled across the

muddy track leaving a bloody trail. Little John looked down at him. “Give him

mercy, Rob,” John asked. “More than he gave Maude,” replied Robin in

the Hood. He reversed his blade and ended all Tod Gallows’ troubles in this

world. Then he looked up at the men who’d followed Gallows. “Any more?” “Next one fights me,” offered Little John.

There were no takers. Little John and Much the Miller’s Son

divested the crestfallen robbers of their weapons and goods. Burly David of

Doncaster, three-times winner of the midsummer wrestling matches in his native

city, and Gilbert Whitehand, as proficient with cleaver in combat as he was

when he cooked the outlaws’ supper, came to assist. Will Stutely led Robin’s archers from the

trees, bringing with them the bound ambushers they’d captured; but the old

outlaw knew enough to leave a couple of men posted watch. Robin had just given

a potent demonstration of the need to keep a check on what was happening

behind. “What shall we do with these bravos and the scum you caught here?”

Stutely asked. “Don’t let them join us,” John advised.

“There’s none of ‘em I’d trust with a knife behind me and they’re all as bad as

their leader.” “They won’t be joining us,” Robin assured

his men. “But we’ll take them along with us. I have another use for them.”

ir Guy of

Gisborne tested the chains that held him. They were strong and new. The outlaws

knew their business. “Where am I?” he demanded now the hood had

been dragged from his head. He was red-faced and half suffocated. “Answer me,

peasants! Where have you taken me?” A fat friar perched on the low wall at the

front of the pig sty where they’d shackled the Prince’s courier. “I thought

you’d recognise a pen for swine,” said Brother Thomas – better known as Tuck. “You let me go now!” ordered Sir Guy.

“Release me and I might yet be merciful.” Friar Tuck finished the chicken leg he’d

been gnawing on and threw the remnant to the fat black sow in the adjacent

stall. “Merciful like you were to the villages you wrecked? Like you were to

the headman at Kinsley? Like you were when your ordered Kinsley

burned? I don’t think I like your mercy.” “Like it or not I’m an envoy of Prince John

of England. Restraining me is treason, and you’ll die bloody for it. Hot coals

and quartering until you beg to die.” The monk sniffed the top of a wineskin. He

seemed to find the aroma satisfactory since he allowed himself a generous sup.

“I don’t serve Prince John,” Tuck told the black knight. “My Prince isn’t of

this world and he doesn’t need to burn villages to command the hearts of his

subjects. But keep on giving orders. It’s not every day I’m threatened by a

naked madman in a pig-sty.” Yesterday Gisbourne had gone to battle

against Robin Hood. His great mistake had been taking his soldiers into the

forest. Now he was captured, stripped and beaten and chained in hog-filth. He

tried his bonds again but the back wall of the enclosure was stone, maybe even

old Roman work, and the ring that secured his shackles was firm and unmoveable. “Every servant of God has a duty to the

crown,” Gisbourne persuaded. “And even a holy friar could benefit from the

reward a Prince would give.” “You think the Prince will want you back,

then?” Tuck wondered. “Robin and I were a little bit worried about that. You

see we’re not convinced that John Lackland thinks enough of any of his minions

to actually pay out good coin for them – and Robin has such good uses he could

put your ransom to.” “Bribing the poor?” sneered Sir Guy.

“They’ll take his money then turn on him with their next breath.” “What he gives them’s better than coin,”

Tuck promised. “I’ll see him dead. I’ll see you dead. I’ll

be revenged.” “Not if there’s any justice in this world,

you won’t,” replied the monk. He reluctantly sealed up the wineskin and tucked

it at his belt. “Prince John’s justice rules this land

now,” Gisbourne warned. “You’ll learn it at your cost.” “In Sherwood we look to Robin Hood for

justice,” declared Friar Tuck. “You’ve already learned that to yours.”

sdric the

Gatherer left Scaftworth on time, his wagon full of the tithes and taxes he’d

taken for the Sheriff. The hard stares of the villagers meant nothing to him.

He was well protected by a dozen armed guards who’d not hesitate to break the

head of any serf or peasant[1] that got in

his way. Besides, the men of Scaftworth had plenty of reason to wish him ill

after this visit; the new Sheriff of Nottingham had been very clear that he

wanted no quarter given to defaulters. The last house in Scaftworth was a little

way outside the village hedge, a small holding rented by a farmer named Dain.

He was due to render nine shillings[2] for his

tenancy and one penny for every sheep, pig, or goat, and for every dozen

poultry. Another two shillings bought him the right to brew ale and bake bread. There was no sign of life around the wooden

farmhouse. Esdric was hardly surprised. Being out when the taxman called was an

old ploy. Sometimes when the gatherer was in a hurry it even worked; the

collector would seize some item of approximate value – a sheep or a butt of

ale, say – and take that without looking to an exact accounting. Sadly for

Dain, the Sheriff’s affeeror[3] had been

very clear that this time every household paid by the book. Esdric hammered on the door so hard it

almost came off its bindings. “Open up in the Sheriff’s name!” shouted the

taxman. “Open or I’ll send for fire!” That usually worked, and this time it was

no different. Esdric heard the sound of a bar being slid away and the door

opened a fraction. “What is it?” asked a frightened woman peering through the

gap. Esdric kicked the door back so the woman

had to step aside or be hit by it. She gasped and retreated a pace, allowing

the taxman onto the threshold. The interior of the hovel was dark and pungent

like all those peasant huts. “Who are you?” the woman demanded, looking

over Esdric’s shoulder at the guards flanking him. “I’m the Sheriff’s man, here for what he’s

due. Who are you? Where’s Dain?” The woman bit her bottom lip and looked

stricken. “Dain’s dead. He caught a fever these three months since. I’m his

wife. His widow.” She looked up defiantly. “I holds this land now.” Esdric shook his head. “Not without a writ

of transfer, you don’t. There’s a body tax to be paid on all Dain’s goods and a

new charter to be bought to carry on tenure. You should have talked to the

steward and the affeeror long before now.” The woman looked stricken. “More fees?

But…” she bit back tears. “I’m hardly holding on as it is. It’s so hard. I

can’t pay no more!” Esdric regarded the widow. He hadn’t even

known Dain was married. Dain’s wife was a deal younger than the dead farmer,

perhaps twenty, and she was a good looking piece. “It’s the law,” the tax-collector observed.

“You have to pay. And now there’ll be fines, too, for not keeping to proper

procedure.” “F-fines? What fines?” “That’s for the court to decide,” Esdric

told her, “based upon my recommendation. Ten shillings, perhaps, or a year’s

income.” The widow trembled. “I can’t pay that! I

don’t have it.” “A flogging then, and cast out onto the

road.” The pretty woman stared at the floor,

desperate and floundering. “What shall I do? What can I do?” she asked herself.

She began to cry properly. Esdric stared openly at her ample bosom as

it trembled at her sobbing. “Well, it’s on my recommendation, as I say. I have

some leeway to help you.” The widow looked up hopefully. “You do? You

would?” “I might,” the tax gatherer offered, “but

you’ll have to convince me.” “Convince you how? Oh…” Now the woman

understood his meaning, recognised his expression. She bit her lip again and

looked away. “Well then…” she said slowly, “you’d better come in.” She stepped

away from the door, retreating into the blackness. “Take a rest for a while,” Esdric told his

grinning guards. “I’ll be examining the estate.” He slipped into the hut’s

interior and barred the door. “And now, my little darling…” Robin Hood pressed a blade to his throat.

“Yes, my sweetheart?” he replied. “Don’t make a sound or my big friend here

will tear your head off.” “And spit down your neck,” offered Little

John. Behind them Ros of Waltham shed her role as

Dain of Scaftworth’s widow and brought forward ropes to bind the taxman. “I

don’t really fancy you,” she told Esdric. “Eyes too close together and a breath

that reeks.” Esdric didn’t dare protest as Little John

hogtied him. He was laid at the back of the hovel beside another bound prisoner

that he recognised as the farmer Dain. “What are your guards’ names?” Robin

demanded. “The two big fellows you had by the door?” “Hardstan and Rufus.” “Call them in. Don’t let them think there’s

any reason to be suspicious. If there’s a fight Ros will prick your eyes out

with her poignard.” “I will an’ all,” promised the outlaw

woman. “Bring them here,” Robin ordered, sliding

the bar back. Esdric had no choice but to obey. The two

guards entered the dark hovel and were overcome before their eyes even adjusted

to the gloom. “And so on,” grinned Robin in the Hood.

“This guard captain calls in more men and we keep going until they’re all our

guests. And then we’ll see about a little bit of accounting.”

can’t believe we did this,” Little John

admitted as the last of Esdric’s party was hobbled and tied in Dain’s hut. “I get that a lot,” admitted Robin Hood.

“But we’ve taken an armed tax train without a single drop of blood shed and I

consider that a good day’s work.” “I’ve never robbed a taxman before,”

admitted Ros proudly. “It’s nice.” Robin imitated a bird call to summon Much

and David from the woods. “Get the wagon out of here,” he told them. “Herd the

confiscated animals into the forest too for now. We’ll return them when the hue

and cry’s died down.” “Right you are, Robin,” agreed the miller’s

son. He’d never doubted that the plan would work. His faith in Robin was

absolute. “Where do you want those bandits we took earlier?” “Have Stutlely bring ‘em here and truss

them next to Esdric’s guards and scribes. It’s going to get quite crowded in

this little hut.” The young outlaw pondered for a moment then ordered that Dain

be dragged outside. He waited until the bound peasant was out of sight of the

prisoners before cutting the man loose. “I can’t believe you did that,” said Dain

of Scaftworth. “He gets that a lot,” laughed Little John. “It’s done, anyway,” Robin said. “If anyone

asks we took you outside to beat you till you told us where you’d buried your

hoard. We’ll be long gone before anyone even starts to look for us. Nobody can

blame you for what we did today.” “They’ll find a way,” Dain predicted

gloomily. He looked over at Ros hopefully. “You could leave that one behind if

she’d a mind to play my wife any longer.” Ros chuckled as John bristled. “I’ve

already got one baby to look after in the forest,” she told the farmer. “And

enough men to wash and sew for till we’ve found more womenfolk who need a

refuge. I don’t know as I’d make a good farmer’s wife any more.” Dain eyed the pretty widow regretfully then

turned back to Robin. “You’re really going to give those goods back to the

village?” “To all the places Esdric took from,” the

young outlaw promised. “Look for a fat wandering friar in a few days time when

the hue and cry’s died down.” “Why?” asked the farmer. “Because there’ll be searches when the

soldiers respond at last and they can’t plunder what’s not here.” That wasn’t what Dain had meant. “No. I

mean why are you giving us our things back? It makes no sense.” “That’s what I keep telling him,” Will

Stutely chipped in. “I mean, we could live like kings on a haul like this. A

few more jobs as successful and we could retire, clear off to Lincoln or York

and start a new life, all set up like. But no, Robin i’ th’ Hood has to go

giving to the poor.” “We’re hungry but virtuous,” Robin teased

the old bandit. “We’re storing up our riches in heaven.” “I’m sure Tuck would be able to tell you

why that’s not quite right,” puzzled Little John. “But it does feel good to be

able to help folks.” “Stealing from the Sheriff,” shuddered

Dain, “He won’t like it.” “He’s welcome to send me a very stern

letter,” answered Robin in the Hood. “Oh, and speaking of letters, I’ve a

missive that needs to go to the good Sheriff as well. When you finally manage

to ‘break free’ from your ropes I’d like you to give it to Esdric to pass on.” “A bandit is sending letters to the Lord

High Sheriff?” “It’s hardly a love letter,” Little John

revealed. “More by way of a ransom note.” “That Guy of Gisbourne,” guessed Dain. Word

travelled fast between the villages and Robin Hood was hot news. “They said as

how you’d taken him alive.” “We should have hung him high for what he

did to our brothers and sisters,” grumbled Stutely. “We still might if we don’t get silver for

him,” Robin declared. “But really right now he’s worth more to us alive than

dead. His ransom will comfort a lot of widows and orphans – and maybe help out

Marion with her brother’s fine.” “I can’t just hand in a ransom note to the

Sheriff of Nottingham,” objected Dain. “They’d put me to the rack.” Robin held up a finger to stop the farmer’s

complaint. “They won’t torture you. They’ll be too busy rewarding you.” “Rewarding me?” Robin gestured back to the crowded hovel.

“The men we just stacked in there on top of Esdric and his thugs are the gang

that ran with Tod Gallows, the brave boys who ravaged Maude of Serlby. They’re

outlaws all with prices on their heads. Turn them in. When the reward’s paid

keep your fair share and pass the rest on to your neighbours. Handing in a

score of murderous raping cut-throats should make sure you’re in good standing

with the Sheriff.” “It… probably will,” agreed Dain, his mind

slowly catching up with Robin’s agile wit. Little John laughed at the farmer’s

expression. “He’s got that look on his face, Stutely,” he noted. “The one we

all get when Robin tells us his plans.” “The one when you realise

it’s too late to escape?” Stutely quipped back. “I know it well.” Robin glared at them with mock annoyance. “Don’t you two have some banditry to do?” *** *** [1] Serfs or

villeins were men and women “tied” to the land they worked, the lowest social

class above actual slave. The majority of people in England in 1190 were serfs.

Their property and lands all belonged to their feudal lord. A serf could not

move from his estate nor even marry without his lord’s permission. A peasant

was a free man of humble stock, and had more rights in law than a serf but was

still subject to a landlord’s will. [2] A shilling

was twelve pennies, roughly two weeks’ wages for a basic hired labourer. At this

time the economy still functioned largely on barter so most taxes were paid in

goods to the value of the amount due. [3] An affeeror

was an official appointed to ensure that court fines were paid, but they also

kept track of taxes due and other legal obligations. |

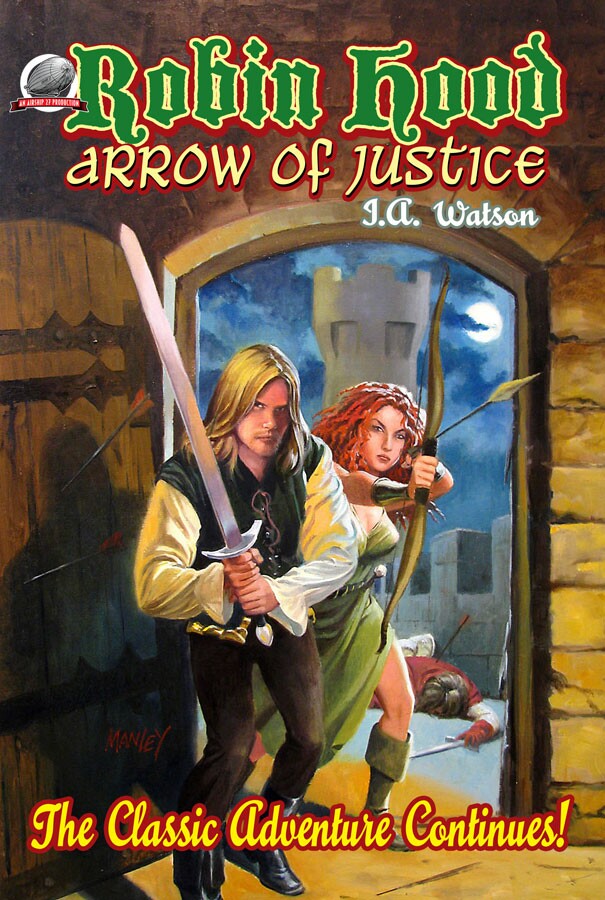

Continued in "Robin Hood: Arrow of Justice"

Continued in "Robin Hood: Arrow of Justice"