|

Where Stories Dwell  The Duke of Marlborough, swashbuckler, soldier, adventurer, and ladies’ man Medea of Colchis, seductive sorceress and woman scorned Eleanor of Aquitaine, the most powerful woman in Europe Brutus Giantslayer, who overcame Gog and Magog to found a nation William Paget, Earl of Uxbridge, and especially his right leg Princess Enheduanna, High Priestess of the Moon Goddess Nanna William the Conqueror, a bastard by name, birth, and nature Sir Francis Dashwood, wicked master of the wicked Hell Fire Club King Arthur Pendragon, rightwise born King of All Britain Kings Henry II, IV, V, and VIII, who average to King Henry IV¾, plus a guest Edward Rhodopis of the Stolen Slipper, a damsel in distress with familiar problems Acting Major William Martin, a Royal Marine who died before he was ever born Inspector-General James Barry MD, a military surgeon who never existed at all Spring-Heeled Jack, fire-breathing iron-clawed terror of the night The Lone Ranger and Tonto

***

1. A Slipper of the Tongue A young girl loses her father. A

tragedy. Her

stepmother abuses her. A crime story. Her godmother grants her wishes. A

fairy tale. She

meets the man of her dreams. A romance. She vanishes from him at the stroke

of midnight. A mystery. He

finds her despite nefarious attempts to thwart him. An adventure. The

lovers are reunited, the evil are punished, and the deserving live happily ever

after to the end of their days. Any

story, even the ones we learned in our cots, can be told many different ways.

When Charles Perrault first recorded Cinderella in 1697,[1]

he was not writing for children but to entertain a sophisticated courtly

audience in Paris’ salons. Jacob and Wilheim Grimm’s version[2]

was at least in part a revenge drama; the stepsisters and their wicked mother

all faced horrible punishments for their behaviour. Or else the story shows

that true breeding and “the right stuff” show through despite rags and

circumstance; the nobility are innately noble. Or else it teaches that a

selfless act of kindness to an old woman can sometimes be wonderfully rewarded.

Or it’s an archaic throwback to a time when women were defined by the men who

rescued them. Or in post-modern versions, it’s about a spunky heroine who takes

her future into her own hands and carves a destiny. Stories

are how we shape our world around us, and how we are shaped. Cinderella

wasn’t the first girl to have a magic slipper, of course. Italian poet

Giambattista Basile collected children’s stories for his Pentamerone (1634-1636),

and included an account of Princess Zezolla, who was abused by her governess’

daughters and turned into a kitchen slave, but who met and fled from a king and

was recognised again by the footwear she had lost. Miscellaneous

Morsels from Youyang, written by Duan Chengshi around A.D. 860, tells of

hardworking orphan Ye Xian, who is helped (by a fish who is a reincarnation of

her mother, a recurring trope of Eastern stories[3])

to attend the king’s banquet, where she leaves her slipper. The king seeks her

out, frees her from her murderous stepmother and stepsister, and makes her his

wife. Go

back further. Strabo’s Geographica, Book 17, 1.33, written between 7

B.C. and A.D. 23, recounts the life of Rhodopis of Nautcratis in Greek Egypt.

Beautiful fair-haired foreigner Rhodopis (her name means “Rosy-Cheeked”) was

despised by her fellow slave-girls, all the more so when her aged master gave

her ruby-coloured slippers for her skilful dancing. When Pharaoh Ahomose II

invited all to a great celebration in Memphis the other girls piled Rhodopis

with chores so she could not attend. As the girl was scrubbing clothes in the

river an eagle snatched her slipper. The bird flew off with it and dropped it

into the pharaoh’s lap. “Stirred by the shape of the sandal”, the king sought,

found, and wed its owner.[4]

Remarkably,

Herodotus’ Histories (450-420 B.C.) also mentions a Rhodopis as a

Thracian slave of Iadmon of Samos – the man who also owned Aesop of Fables

fame! She was taken to Egypt by her new master and freed for a huge sum by

Charaxus of Myteline, brother of the poet Sappho.[5] But

there’s more. The sixth dynasty of Egypt is currently dated as ending in 2181

B.C., but its possible final queen, Nitocris, has been expunged by modern

archaeologists and historians as being a probable fiction. This is the young

woman, who, according to Herodotus, took decisive action after the murder of

her pharaoh brother by inviting all those who had conspired to a banquet to

dedicate her new feasting hall then flooded it and drowned all those within.

Manethon, Egyptian historian and priest from Sebennytos during the 3rd century

B.C., attributes Nitocris with building the third pyramid (other historians may

vary). And

Herodotus goes out of his way to tell us that all rumours of Rhodopis building

the third pyramid are wrong.[6]

Yes, there were popular associations between Rhodopis and Nitocris, so strong

that the scholarly historian felt obliged to prove them erroneous in his text.

Or, to put it another way: Cinderella built a pyramid. Nitocris

slinks into pulp fiction again in Lord Dunsany’s play The Queen’s Enemies,

in H.P. Lovecraft’s stories “The Outsider” and “Imprisoned with the Pharaohs”,

and in Tennessee Williams’ “The Vengeance of Nitocris”. In Lovecraft’s second

tale, written in the first person for Harry Houdini, the escape artist

encounters the undead queen of shambling human and animal-headed mummies.

Cinderella, mistress of the undead. John

Basalt’s 1929 novel Der Blau Basalt, translated to English as Nile

Gold, was the first modern work to resurrect the Rhodopis/Nitocris

connection. It speculates that Rhodopis became Queen Nitocris by marriage to

the pharaoh who found her slipper. But,

as Herodotus concludes before moving on, “This is enough about Rhodopis.” For

at least two and a half millennia, oppressed girls have been losing footwear

and royal suitors have come to return it. In 1893, the Folklore Society of

Britain identified 345 variant versions of the story.[7]

In the Philippines, misused Maria is helped by Mariang the crab. Malaysian

Bawang Merah, enslaved by the stepmother who killed her parents, is guided to

her prince by the bones of a fish that her mother’s spirit occupied. In

Vietnam, downtrodden Tâm Cám is likewise helped by a dead fish to boil her

stepsister alive and feed her to her stepmother. Kongjwi in Korea, Ashenputtel

in Germany, and the youngest sister in “The Eldest Lady’s Tale” from 1001

Nights are all different takes on the same basic events. This

tells us two things; three if there’s a lesson to be had about carelessness

with slippers. Firstly, a good story lasts and travels. It’s a tool that is put

to many uses as circumstances demand. Secondly, the way we use the story

tells us quite a bit about ourselves, our values, our culture, and our

character. This

volume is about stories. It has plenty of stories in it, from ancient myth to

biographies of some great eccentrics, from ghostly mysteries to neglected

histories. But it’s also about telling stories. How we tell them. Why we tell

them. What are they for? I

don’t have any great revelations to offer. Then again, understanding stories

isn’t a matter of revelation so much as inspiration. Once one can see our

consensus reality as one defined by the words by which we name things and the

stories by which we contextualise events, then one knows why the pen is

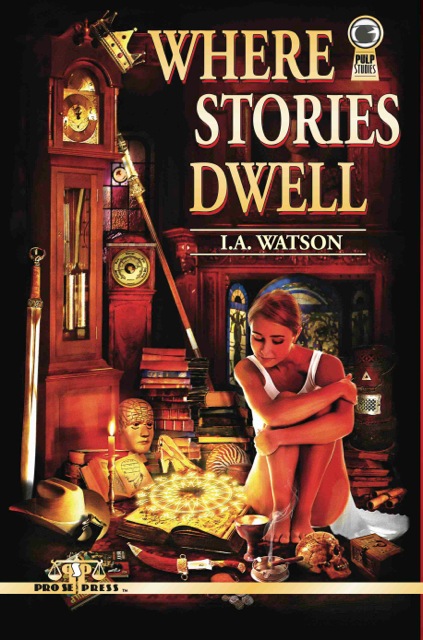

mightier than the sword: swords can only kill you; words can make you immortal. Squeezing the Pulp Pause for

a moment and inspect the cover. Authors don’t

usually get much say about what goes on there, but Pro-Se is usually pretty

good at that stuff. I’m willing to bet there’ll be a publisher’s logo for on it

somewhere though, and if you know Pro-Se you’ll know they’re a small, hungry,

growing publisher that mostly specialises in pulp fiction.[8]

They must be pretty smart too – they printed my stuff![9] The

point, though, is that Pro-Se is at the vanguard of the New Pulp movement, the

great revival of techniques and traits, and sometimes of the characters and

situations, that reached its most prominent peak back in the cheap

mass-produced monthly magazines and dime-store novels of the 1930s. The stories

in those old publications had to grab the reader by the throat and bring them

back next time. They had to make the purchaser feel his hard-earned two bits

had been well spent. And to achieve that, those pulp writers had to dig deep into

stories and come up with the undistilled stuff. Pulp

was visceral, demanding an emotional reaction from the reader. It was popular,

in both senses of the word, being cheaply mass-produced for a large audience

and being aimed at the masses rather than the elite. Rising from the ‘penny

dreadfuls’ and monthly gentleman’s magazines of the Victorian era – which gave

us such pulp characters as Sherlock Holmes and Allan Quartermain – pulp

literature spawned much of modern popular fiction. Many

of our most recognised media “franchises” are rooted in that era. Some are

directly from it – James Bond and Tarzan, for example, along with every

hard-boiled street-pounding ‘tec and high-flying space adventurer. Others

merely owe their existence to the tropes popularised in that period; Star Wars,

Indiana Jones, Batman, take a bow. Don’t

worry, we’ll bring that cast back later in the book. The

conditions that led to the growth of the pulp genre back then were the

development of a new mass market through cheap print publishing; bleak economic

circumstances developing an audience appetite for worlds where justice

prevailed, however rough, and where heroes tackled villains; and a thirst for

escape from “the real world” into the entertainment and catharsis of a good

story. Strangely,

those are conditions that might be said to prevail as much in the present age

as in the 1920s and 30s. A new mass market has opened with the arrival of

online book sales via Kindle and Amazon and their competitors. In 2011 my book

royalties reached the tipping point where more income comes from e-sales than

from paper copies; other authors seem to echo my experience.[10]

We are currently enduring global recession, with the consequent disillusionment

in our institutions and leadership that makes fictional characters seem our

only refuge for integrity and heroism. And our Western society has become

obsessed with stories again, from TV and movies to video games and comic books. This

is where the “new” part comes in with “new pulp”. There’s

a fresh growth of publishing with the internet age. The balance of power has

shifted from the bookstores to the internet, from the big publishers to the

self-publishers. The old paradigms have crumbled. We mourned the loss of local

bookstores decades ago, but now we’re seeing even the national chains begin to

vanish; and yet book sales haven’t massively diminished, only shifted to other

sales venues.[11] The next

generation of household name authors won’t be “discovered” by a literary agent

and signed-up for life by a major imprint, they’ll rise from the talent using

CreateSpace and Amazon Kindle and all the other ways there are now for writers

to sell print-on-demand or electronic copies of their work. And

somewhere in that list will be some of the luminaries of the New Pulp wave. Or

it might be the Genre Fiction wave. Or the Slipstream wave. The terminology

arguments can go on forever. What its harder to argue about is that pulp, noir,

whatever term wins dominance in the end, is back to stay – and its all because

of the story. So another thing you’ll notice about

this book is that it keeps harking back to the pulp genre. Partly that’s an

artefact of this volume’s origin. Much of the material included herein first

circulated privately to a list of pulp fiction writers (see the dedication

page) and so was slanted to their interests and experiences. The book itself is

published and distributed by a pulp publisher. But I hold that pulp is itself a

throwback to some of the earliest forms of storytelling, to fairy tales and myths,

and that the three things naturally go together. I’ll try and convince you as

the stories pile up. For

now, let’s just remember that pulp also describes 1. a recycled product and 2.

the stuff you squeeze out when you really want some refreshment. Stories vs. Atoms Put two

people in a room for long enough, and if they

don’t kill each other they’ll start to tell stories. They’ll probably start by

saying their names – names used to tell stories themselves; ask Mr Smith, Mr

Weaver, Mrs Tanner, Ms MacDonald. Then they’ll say what they do for a living.

Then they’ll share something about their family. Stories. As

far back as humans can remember, and probably further than that, we’ve been

telling stories. Ask Cinderella. Don’t

ask the semiotics. They’ll talk about signs as the building blocks of meaning,

then discuss semantics, then describe how signs combine in codes to transmit

messages in a discourse of varying modalities and forms. No offence to

well-meaning academics doing valuable work into language and psychology, but

deconstructing stories to find what they’re about is like performing an autopsy

on a cadaver to find the soul. Consider

instead this story: During

the earliest days of Soviet rule in Communist Russia, a good deal of effort was

put into stamping out the Orthodox Church’s grip on the peasantry. Clever young

Party men were sent out to lecture on the follies of religion and the virtues

of the state, so that the masses would understand that they had been freed from

the tyranny of theology. One

such meeting took place on a snowy Easter Day in some rural village, in what

had been the church hall. Every member of the community was expected to attend.

The distinguished visitor spoke for upwards of three hours on Marxist ideals

and the benefits of atheism. When he finally finished his proofs that God did

not exist he asked, nay challenged, his cowed audience if they had any comment. The

parish’s former priest stood and spoke only three words: “Christ is risen.” Whereupon

the entire assembly rose and replied to the traditional Easter proclamation

with the traditional response: “He is risen indeed!” Now

I’ve heard this story told in church as testimony to the faith of

religiously-oppressed people. I’ve seen it repeated in text as proof of the way

the church brainwashes its adherents. Many people are sceptical of the tale’s

veracity; after all, no specific time or place is mentioned and there is no

mention of the aftermath of such civil disobedience. It sounds like a parable

suitable for an instructive homily. The

point is, though, that the story has resonance. Religious or not, it demands a

response of us. No dissection of the relationship of form and style[12]

really gets to the bottom of why. No listing of the tropes the story has

in common with other narratives[13]

helps explain why we have to listen to it. In fact we only understand the story

by experiencing the story; that is to say, hearing it and thinking about what

we hear. Stories are a very sophisticated

type of communication. They are excellent teaching tools because they give us

associations and context for important information (“And that’s why we don’t

cry “wolf” when there’s no danger, children!”). They reinforce social behaviour

and create community identity (“And so it is that we never eat the flesh of the

pig”). They form our opinions (“Now Goldilocks knew that she shouldn’t go into

the house…”). They influence our expectations (“He saw her and fell in love at

once”). Consider

wallpaper. I once had to redecorate my bathroom entirely because, as I was

soaking in the tub one day, I realised that there were faces in the patterns.

And they were watching me. Now once you’ve made random blobs into a face you

can’t un-see it. Ask all the people who find Elvis on a burger bun or the

Virgin Mary in a damp stain. So the wallpaper had to go, and my baths could

again be private. Seeing

faces where there are none, seeing monsters where no monsters lurk, are both

primitive survival techniques. Its better to have a hundred false alarms, where

the primitive proto-human startles at nothing, then to miss one alert where the

predator is real. Evolution has given us pattern recognition. Our

developing cognitive processes and memory capacities have given us non-visual

pattern recognition as well. Now we can draw associations and extrapolate from

them. At its simplest, the story we work out for ourselves probably started out

as: “Well, the day before yesterday the tasty game animals came to this water

to drink. Yesterday the tasty game animals came to this water to drink. Perhaps

then the tasty game animals will come again today. Where’s my spear?” From

that we go on to personal stories and family histories, to tales that explain

the world and tales that simply amuse, and from there to the whole body of literature

that defines mankind. But

when I see a face in the wallpaper, I’m not really seeing a face. It’s not

there. Neither is the wallpaper. Neither is the wall. Zen,

huh? But since physics insists that solid matter isn’t solid, just a bunch of

subatomic particles with vast spaces between them, coupled with strong and weak

forces, bouncing photons back to specialised electrochemical cells in my

eyeballs, then what we see isn’t what’s really there. It is, in fact, the story

our brain constructs for us so we can understand and cope with what’s there. On

a fundamental level, reality as we perceive it is determined by the narrative

we put to it. Change the story, change the universe. *** 2. Babbling, or History’s First Author Without

language there are no stories. There are no

lies and no truths. Without language we cannot name the world to understand it

and control it. Humanity

is distinguished from the rest of life on Earth because we have a sophisticated

method of communicating ideas, information, history, feelings, instructions,

even objections. When things go wrong, the voice of reason says, “Let’s talk

this over.” The

ancient sources of the Bible understood the importance of language. Whether one

chooses to believe that the priests and prophets who first wrote those texts

received dictation direct from God or distilled many generations of diverse

folklore into a single unifying narrative, those Jewish texts reflect the

importance of words in creation. “In

the beginning, God said…”[14] “God

also gave Adam the gift of naming the things of the universe.” [15] “You

shall not take the name of the LORD your God in vain, for the LORD will not

hold him guiltless who takes his name in vain.”[16] The

first story in the Bible that’s really about words, about language, is found in

Genesis 11, 1-9. But before the theology, a little geology. The

Middle East was, of old, defined by two rivers. The Tigris and the Euphrates

run south through arid desert, transforming the locality through which they

drain into lush fertile corridors. In ancient times, annual river floods

irrigated pasture nearby, allowing a thriving early civilisation to rise up on

the Akkadian delta. Archaeologists agree with historians on that one. The

most effective form of survival was to cultivate local resources, which meant

herding and farming. Success meant the population rose, which meant that

resources had to be contended for. Humans banded together for mutual defence

and because it allowed specialisation. A man who knew how to make pots well could

make pots all day and exchange his pots for another man’s fruit or meat.

Specialisation requires trade, and trade requires marketplaces, and

marketplaces cause villages. And villages are targets, so they require

soldiers, another specialised trade, and as those settlements get wealthier and

larger they require walls. And suddenly there are cities. That

part of the world was short of some resources, though. In particular, wood was

scarce and stone was hard to quarry. The natural building materials of much of

the world were difficult to come by, but one thing the inhabitants by the

Tigris and Euphrates had in plenty was mud. Make

a box one cubit long by half a cubit wide and deep – a cubit is the length of a

man’s arm from elbow to middle fingertip, around eighteen inches, and its one

of the oldest measurements. Fill the box with river mud. Toss in some straw for

texture if desired. Leave it to dry in the blistering sunlight for a couple of

hours. Tip out the brick that solidifies in that time and you’ll have a

building material that’s pretty durable. In fact it can withstand weight from

above as well as some types of rock. The

Akkadians built their villages, then their towns, then their walled cities, out

of mud brick – which is fine until you have a Flood. I

don’t mean a flood, the seasonal descent of waters drained from higher land.

I’m talking Flood, the sort of thing that Bible described in Genesis

6-9. Another

thing geology has confirmed for us is that the Tigris and Euphrates have, from

time to time, modified their courses after major cataracts. This might have

been natural or it could have been one of the world’s first man-made

eco-disasters. As

cities grew along the riverbanks, with rising populations competing for limited

arable land, some unrecorded genius had the idea of digging a trench from the

river out into the desert, bringing the life-giving water to turn barren waste

into farmable plots. The science of irrigation was born. Canals were cut along

the lengths of the great watercourses, extending the seedable and grazable

lands far beyond the half-mile corridor that had previously confined

civilisation. The

cost of those channels was that the natural riverbanks had to be compromised,

allowing water onto the flat plainlands beyond. When the floods rose again

there was no defence. If

you don’t take a fundamentalist view that the Biblical Flood happened because

God simply dropped a lot of water, here’s a mechanism by which “all the lands”

might be covered. After all, as Einstein contended, “Coincidence is God’s way

of remaining anonymous.” In any case, it could be argued that with their

increased prosperity and a science that had overcome nature and brought about

an age of plenty, the Akkadians felt that they no longer needed God to send

them the necessary things of life. Their hubris was their downfall. The

story of the Great Flood appears in many mythologies. The Sumerian King-List

distinguishes between the massive longevities of rulers before the Flood and

the mortal spans of those after. The Biblical account of Noah is similar to the

story of Utnapishtim in the Epic of Gilgamesh. A variant account appears

in the Yazidi Mishefa Reş. Hindu texts such as the Satapatha

Brahmana mention a man escaping a great deluge in a boat by intervention of

Vishnu. Quiché, Mayas, and Greek mythologies likewise feature survival of great

floods. So

the cataracts came; and mud-bricks, while excellent for holding up buildings

against wind and weight, are useless when submerged by rising waters. Mud

bricks + river = mud. No wonder the Flood washed away all the cities of the

Earth. Anyway, in each of the stories the

waters eventually passed. The ark’s survivors emerged from their boats and

began to rebuild and repopulate the land of the two rivers. But as time went on

they either forgot the lesson of the past or had a very human reaction to it. If

God had caused the Flood in response to human sin and might do so again

(rainbows notwithstanding) then there were two possible responses: 1. Do not

sin. 2. Get rid of God. Hence

the Tower of Babel, that amazing folly described in the eleventh chapter of

Genesis[17],

in that first story about language. The

Babylonian cosmos-view, and probably that of the whole Middle East in ancient

times, held that the Earth was positioned over a void, possibly the abode of

the dead, in a vast and eternal sea. Above us was the canopy of the stars, a

frame or series of frames upon which sun, moon and planets wheeled. A great

dome of the sky was the final starry backdrop. On the other side of that was

heaven, the dwelling place of God. So,

taking that as a scientifically proven given, it is perhaps not too ridiculous

to plan a huge high tower that can be built all the way up to that celestial

canvas. A little cutting work on the cloth of the universe and an invasion of

heaven becomes very feasible. Why not organise a pre-emptive strike against God

before he can send another Flood? Or,

if you prefer a more allegorical reason for the Tower, it was an expression of

human dominance, an “in-your-face, God,” defiance; or a temple to some pagan

fire deity requiring human sacrifice; or a political statement demanding the

unification of all peoples of Earth under a single authority. Commentaries

vary, and have done since the Jewish Midrash. In

any case, the myth insists that a great tower was raised at Babel (what we

would call Babylon in ancient Mesopotamia, modern day Iraq), and it was pretty

damned high, and it was pretty bothersome to God.[18]

In fact the Bible records his response as, “Behold, the people is one, and they

have all one language; and this they begin to do: and now nothing will be

restrained from them, which they have imagined to do.” It

also described His response. “Go to, let us go down, and there confound their

language, that they may not understand one another’s speech.” Later

sources describe the Tower’s spectacular destruction, where the top part is

consumed by fire and the bottom crumbled into the earth, but the Genesis

account says nothing of that. Confounded by God giving them not one but many

languages (and by implication many cultures, beliefs, and world-views), the

builders could no longer co-operate and so abandoned their efforts. The Tower

fell because of the birth of politics, or sectarianism, or arguments about

definitions. Language

defines the world. A culture with no word for “apology” can’t have any concept

of it. Another might invent such a useful word, for example schadenfreude, that

it has to be adapted into other languages so the concept can be properly

expressed. How interesting that the world’s most internationally recognised

word, okay, was unheard of a little over a century and a half ago.[19] Maybe

we’re getting to the point where we can build Babel again. Perhaps if we build

it the right way this time it won’t be displeasing to God. That’s

our story and we’re sticking to it. The World’s First Writing Credit Who was the world’s first author? More properly, who was the first author who included a name

on their work, “signing it”? The first known, named author, poet, epic-writer, and the first person to attempt to codify theology was... Princess Enheduanna, High Priestess

of the Moon Goddess Nanna[20]

in Ur, somewhere around 2250 B.C. And she didn’t just sign her work; she left

us an “about the author”. In fact Enheduanna is one of the

earliest women in history whose name we know.[21]

She was eldest-born of Sumerian dynasty founder Sargon the Great, and was

daughter, sister, and aunt of kings. She was a very smart, very powerful woman,

exiled for her politicking then returned to power. She’s even got a link to the Tower

of Babel. Her father, Sargon the Great, was a seminal figure in Sumerian

history. He is sometimes equated with Nimrod the Hunter, or described as a

descendant of Nimrod, and many early sources (but not the Bible) place Nimrod

as king of Babel at the time of the tower’s rise and fall. Some historians and

mythographers have attempted to patch a biography in which Nimrod escapes the

destruction of Babel and founds his new empire at Sumer. In any case, Enheduanna understood

words. She is the first woman in history known to have been literate (although

the Babylonian goddess Nindaba was the gods’ scribe, suggesting that writing

things down may have been a common noble female role in that culture). Born in 2285 B.C., Enheduanna was

the eldest daughter of Queen Tashlultum, about whom stories have also been

told. Tashlultum translates as “I carried her off as spoils”. She may

previously have been wife to Uruk’s sole third dynasty king, Lugul-Zaggisi

(other spellings are also available), before Sargon of Akkad came along and

conquered everything. Sargon appointed his daughter as

High Priestess of Ur. It was a smart political move, securing the south of his

empire under the control of a competent and trusted caretaker. Enheduanna took

her duties very seriously and began her writing as part of them. Her surviving

works include the epic and autobiographical Exhalation of Inanna, the

mythological Inanna and Ebih, the fragmentary Inanna sa-gura and

forty-two hymns and poems. It is from Enheduanna that we have a good

understanding of Sumerian myth and culture and some of the earliest poetry and

literature in the world. Of course, Enheduanna is a pen name. It means “High

Priestess, Adornment of the God”. Another first for her. And she’s the earliest

named woman whose image has survived to the modern day. A Sumerian

statue depicts her carrying

the sacred instruments of her office and a head-dress of authority, and

otherwise wearing traditional female Sumerian dress, i.e. nothing. So she may

be the first identified cheesecake too. She does have wings, though. Enheduanna continued her senior role after her father’s

death when her brother Rimush became king. Eventually the siblings quarrelled.

The priestess/princess was exiled, perhaps around the same time that the gods

Enlil and his daughter Nanna[22]

were temporarily banished from Sumerian religious life. She may also be the first person to use literature as a

form of P.R. The clay tablets on which she wrote Exhalation of Inanna, her

autobiographical appeal to the gods against unfair exile, seem to have played

some role in her reinstatement and that of her deity. This was a woman who really

understood the power of words. So, Enheduanna is one of the first women whose name had been recorded to history, and she is the most ancient author whose name is known. Her works include poems, epic narratives, an autobiography, and the first written attempts at systematic theology. She was daughter, brother and aunt to kings of Akkad and the High Priestess of the moon goddess Nanna in Ur. She seems to have been just as formidable and brilliant as one might wish the first writer to have been. *** 3. On Heroes We live in a cynical age where we’ve learned the hard way that

people we’re expected to look up to don’t always deserve our respect.

Presidents and monarchs have dirty secrets. Priests hide sex scandals. Captains

of industry pilfer pension funds and sportsmen take drugs. Not

all of them, of course, but enough to disappoint. Maybe

they always did and we’re just better at finding out now. Anyhow,

the point is that these failures have led us to be cautious about investing our

adulation another time, like someone who’s had a bad relationship and won’t

ever let themselves fall in love again. And

by some weird reverse psychology, that lack of trust gets turned into a “good

thing”. If nobody is a real hero then there’s no pressure on me to be one. If

nobody is extraordinary then it’s okay for me to be ordinary too. If everyone

cheats and lies and looks after number one... Now

our fiction, and especially our adventure and fantasy fiction, reflects two

things: how we think the world is, and how we want the world to be. Sloppy lazy

writers pander to the lowest denominator, peopling their world with the

characters and situations that they believe their readership expects - venal

shabby characters having easy sex and easy betrayals in a world where

honourable people are fools and victims and where protagonists of stature must

have some dark flaw to average them down to ‘realism’. Those

writers betray their own insecurities in their work. They don’t believe they

can ‘sell’ a true hero. True heroes require some suspension of disbelief, and

suspension of disbelief requires writing talent. They don’t believe their

audience has the imagination or nobility or character to accept such a hero. There’s a key passage in Terry Pratchett’s excellent

fantasy novel Hogfather[23]

where his hero, Death (the personification) prevents a plot to stop the sun

from coming up. He’s asked what would have happened if the mythological

creature responsible for its rising hadn’t been saved. “A mere ball of flaming

gas would have lit the world,” he replies. Events stripped of their meaning

lead to a world stripped of any soul. Asked why little fictions (such as Santa) should matter,

Death answers, “You have to start out learning to believe the little lies.” He

explains that they to teach us how to accept the big fictions: “Justice. Mercy.

Duty. That sort of thing...” And then he goes on to argue that unless we can

imagine things that don’t exist we cannot create them so they become real. It’s

sophisticated, life-enhancing stuff for a humorous book, and Pratchett

understands perfectly why we need to write about heroes. If we can imagine

heroes then we can be heroes. If we have heroes amongst us then we’re

challenged to be like them. There’s

a long-forgotten scene in an old Gruenwald issue of Captain America

where Cap catches a kid shoplifting superhero comic books.[24]

He asks how he can read those stories and still think it’s okay to steal. And

Cap is right. I once got in the way of some bullies at school just because I

knew it’s what Steve Rogers[25]

would do. Pulp

fiction often specialises in tarnished heroes. These protagonists have

character flaws - they drink, or gamble, or fall for the wrong girl, or carry

some tragedy inside them. They’ve made some terrible mistake in their past. But

the heroic part of them comes from conquering those flaws, from doing what’s

right despite their limitations. Many live in gritty sinful worlds but do the

right thing at the last in any case. The more limitations, the greater the

heroism to overcome them. Put

another way: a guy who runs a 20 mile marathon for charity is a hero. A guy who

does it in his wheelchair’s an even bigger hero. I

think that as a society we’re starting to appreciate heroes again. It’s a more

mature understanding, perhaps, and it’s slow to form. Maybe for America the

turning point was the rescue services’ sacrifice at the Twin Towers, reminding

a nation what devotion and courage were about. Here in the UK we’ve been

getting a fairly steady stream of military coffins back from Afghanistan and

they’re always flown back to the same air force base, RAF Lyneham. The nearby

village is Wootton Bassett, a small place of 11,000 people. Every single time

those coffins are brought through town those people line the streets in silence

to pay their respects. They see it as their tribute to heroes. Keep

the faith, folks. “Nurture your mind

with great thoughts; to believe in the heroic makes heroes” |

“As you get older, it

is harder to have heroes, but it is sort of necessary”

Hemingway

***

CONTINUED in WHERE STORIES DWELL by I.A. Watson,

available in print and on Kindle. Back to I.A. Watson's author page

***

Content copyright © 2014 reserved by Ian Watson.

The right of Ian Watson to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs & Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved.

***

[1] Histoires

ou contes du temps passé or Les Contes de ma Mère l’Oye (Fairy Tales

From Times Past With Morals, or The Tales of Mother Goose) Charles Perrault,

Paris, 1697.

[2] In

“Aschenputtel” Grimm’s Fairy Tales, 1812, the sisters had “beautiful

faces and fair skin, but hearts that were foul and black”. They sliced off

their heels and toes to try and fit into the slipper but seeping blood betrayed

them They were punished at the heroine’s wedding by birds Aschenputtel summoned

to peck out their eyes (Disney take note), blinding and disfiguring them. Other

versions see the sisters and their mother rolled in tar-barrels or simply

executed.

[3] In some

variants of the my-dead-mother-is-my-helpful-fish story, the heroine is forced

by her oppressor to cook and eat the tutelary familiar. However, she keeps the

creature’s bones and it is they who guide her to her destiny.

Writing

on possessed fish being eaten in some cultures, Robert Graves in The Golden

Bough discusses Indian rituals where such a fish is eaten as a fertility

rite to reincarnate the spirit in a new child. The same ancient Greek word for

fish and womb is delphos, suggesting ancient associations between fish

and fertility; some speculate that this is the symbolism of the mermaid.

[4] Also

possibly history’s first recorded foot fetish.

[5] There are no

slippers in this version. Herodotus is discussing Greek hetaera, those superior

female courtesan companions, educated and erudite, the only women whose

presence was welcomed and well-regarded in the Greek symposia. Rhodopis is one

of only two hetaera he names (the other is Archdyke).

If

historical Rhodopis was indeed an hetaera then Charaxus must have paid a high

purchase price indeed for it to be noted. Demosthenes records that the hetaera

Neiara bought her freedom for 30 minas, perhaps $575,000 in today’s currency.

Sappho

later wrote a poem accusing Rhodopis of conning her brother out of his

property.

[6] The full

quote, from Histories 2.134.1&2 (Loeb) is “Some Greeks say that it

was built by Rhodopis, the courtesan, but they are wrong; indeed, it is clear

to me that they say this without even knowing who Rhodopis was (otherwise, they

would never have credited her with the building of a pyramid on which what I

may call an uncountable sum of money was spent), or that Rhodopis flourished in

the reign of Amasis, not of Mycerinus.”

Several

historians attest that Rhodopis dedicated a great deal of treasure at the

Oracle of Delphi however, which was on display for centuries thereafter.

[7] Cinderella: Three Hundred and Forty-Five

Variants of Cinderella, Catskin and, Cap o’Rushes, Abstracted and Tabulated

with a Discussion of Medieval Analogues and Notes, Marian Roalfe Cox, 1893.

[8] Pulp is a portmanteau team for a genre of

action-oriented character-rich plot-driven writing that provokes gut reactions

in its readers. It is typified by the cheap 1920s and 30s mass-marketed U.S.

magazines such as Weird Tales that popularised the term, but includes a

wide range of sources and is still a popular literary medium today. Horror,

romance, adventure, mystery, it’s all got to get the heart pumping and keep the

pages turning..

[9] Readers are

directed to www.prose-press.com and to the volumes The New Adventures of

Richard Knight and Blood-Price of the Missionary’s Gold: The New

Adventures of Armless O’Neil.

[10]

“Kindle ebook sales have overtaken

Amazon print sales, says book seller”, The Guardian, 6th

August 2012

[11] This is

perhaps contentious. There are all kinds of conflicting statistics out there

for book sales, confused and confounded by commercial confidentiality and

optimistic marketing. Perhaps the most robust US stats come from the Census

bureau, which records year-on-year book sales income as follows: 2002=

$15.45bn, 2003=£16.24bn, 2004=$16.88bn, 2005=$16.89bn, 2006=$16.99bn,

2007=$17.18bn, 2008=$16.87bn, 2009=$16.05bn, 1010=$15.66bn; 2011=$15.53bn.

Codex

Group, which describes itself as “the leader in book audience research and

pre-publication book testing”, released statistics through their website at

http://www.codexgroup.net/ based upon a quarter of a million interviews since

2004. Their research suggests that within two years the percentage of

purchasers who discovered new books in-store has dropped from 35% to 17%. In

the same period, books bought because of personal recommendation rose from 14%

to 22%, of which three-quarters were face-to-face recognition.

[12] This would

be Russian Formalism, Viktor Borisovich Shklovsky’s 1930s work on understanding

narrative.

[13] Morphology of the Folktale (1928, but not translated to English

until 1958) by Vladimir Yakovlevich Propp analysed the basic plot components of

Russian folk tales to identify their simplest irreducible narrative elements.

[14] Book of

Genesis, Chapter 1, verse 3.

[15] Genesis

2: 19-20: And out of the ground the LORD God formed every beast of the field,

and every fowl of the air; and brought them unto Adam to see what he would call

them: and whatsoever Adam called every living creature, that was the name

thereof. And Adam gave names to all cattle, and to the fowl of the air, and to

every beast of the field…

[16] Exodus

20.7, the third of the Ten Commandments; also listed in Deuteronomy 4.11

[17] “And the whole earth was of one language, and of one

speech. And it came to pass, as they journeyed from the east, that they found a

plain in the land of Shinar; and they dwelt there. And they said one to

another, Go to, let us make brick, and burn them thoroughly. And they had brick

for stone, and slime had they for mortar. And they said, Go to, let us build us

a city and a tower, whose top may reach unto heaven; and let us make us a name,

lest we be scattered abroad upon the face of the whole earth.

And the Lord came down to see the

city and the tower, which the children of men builded. And the Lord said,

Behold, the people is one, and they have all one language; and this they begin

to do: and now nothing will be restrained from them, which they have imagined

to do. Go to, let us go down, and there confound their language, that they may

not understand one another’s speech.

So the Lord scattered them abroad

from thence upon the face of all the earth: and they left off to build the

city. Therefore is the name of it called Babel; because the Lord did

there confound the language of all the earth: and from thence did the Lord

scatter them abroad upon the face of all the earth.”

Book of Genesis XI:1-9, King James Version

[18] Many

sources differ as to the dimensions and construction time of the Tower of

Babel, but all agree that it was made from baked river mud-clay and mortared

with bitumen (asphalt), the common construction technique of that part of the

world at that time, and still sometimes used today. For example, the apocryphal

Book of Jubilees 10:20-21 states, “And they began to build, and in the

fourth week they made brick with fire, and the bricks served them for stone,

and the clay with which they cemented them together was asphalt which comes out

of the sea, and out of the fountains of water in the land of Shinar. And they

built it: forty and three years were they building it; its breadth was 203

bricks, and the height [of a brick] was the third of one; its height amounted

to 5433 cubits and 2 palms, and [the extent of one wall was] thirteen stades

[and of the other thirty stades]” (Charles’ 1913 translation). This description

suggests that the Tower was over one and a half miles tall. In 2010 the world’s

tallest building was Burj Khalifa in Dubai, United Arab Emirates, at 2,722 feet

a meagre half-mile high.

Genesis

offers no dimensions but makes clear that the construction never met its

intended height.

[19] J.F.D.

Smythe’s A Tour of the Unites States of America (1784) records a Negro

slave saying, “Kay, massa, you just leave me, me sit here,” from which some

etymologists suggest a West African origin for okay in the Wolof and Bantu word

waw-key or the Mandingo phrase o ke. Other scholars date the work

back to the 1830s Boston comical misspellings abbreviation fad, citing O.K. as

a shortening of “Oll Korrect”. Democrats claim it for its use in their “Vote

for OK” 1840 presidential campaign for Martin Van Buren of “Old Kinderhook”,

New York. This campaign also introduced the “O.K. sign” with the forefinger and

thumb circled and the other fingers raised and curved – possibly the politest

gesture originating in politics. It was fashionable until the 1960s to claim

okay was a borrowed Chactaw word. Others believe the word a corruption of the

Scots “Och aye,” the Lakota “hokahey”, Finnish “oikea”, German “ohne

korrectur”, or the Greek “Ola Kala”.

[20] There are

several variants of the name of the powerful Sumerian goddess of sexual love,

fertility and warfare. The most prevalent is Inanna or Inana. Her Akkadian name

was Ishtar. She shares many correlations with other love goddesses such as

Aphrodite/Venus, including associations with the morning star, with doves, and

with octangles.

[21] The same

source that names Enheduanna also names her mother Tashlultum, who by the

irreductable logic of biology was born first. Other early named women are

Kubaba, a tavern keeper who rose to be the only queen to appear on the Sumerian

King List (because she ruled in her own right, not through marriage to a king),

and Peseshet, a fourth dynasty doctor and the earliest recorded woman of that

profession except possibly the even earlier Merit-Ptah who held the title of

“Lady Overseer of the Female Physicians”.

[22] Enlil’s

origin myth story has been translated from a number of fragmentary tablets at

the University of Pennsylvania, the Museum of the Ancient Orient in Istanbul,

and the British Museum. Enlil ignores the laws of his homeland and seduces or

rapes Ninlil, who bears him a child. When Enlil is banished to the underworld

for his crime (which may have been ritual uncleanliness from pre-marital sex),

Ninlil follows. Enlil disguises himself and when Ninlil asks him if he has seen

Enlil he claims he has not – so she sleeps with the “stranger” instead. Three

more children are successively conceived by this ruse, one of whom is the

moon-goddess Nanna.

[23] Hogfather,

by Terry Pratchett, Corgi, 1997,

ISBN-10: 0552145424, ISBN-13: 978-0552145428

[24] Captain

America #425, Marvel Comics, March 1994, written by Mark Gruenwald.

[25] The

civilian identity of Captain America.

available in print and on Kindle.

The right of Ian Watson to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs & Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved.

[1] Histoires ou contes du temps passé or Les Contes de ma Mère l’Oye (Fairy Tales From Times Past With Morals, or The Tales of Mother Goose) Charles Perrault, Paris, 1697.

[2] In “Aschenputtel” Grimm’s Fairy Tales, 1812, the sisters had “beautiful faces and fair skin, but hearts that were foul and black”. They sliced off their heels and toes to try and fit into the slipper but seeping blood betrayed them They were punished at the heroine’s wedding by birds Aschenputtel summoned to peck out their eyes (Disney take note), blinding and disfiguring them. Other versions see the sisters and their mother rolled in tar-barrels or simply executed.

[3] In some variants of the my-dead-mother-is-my-helpful-fish story, the heroine is forced by her oppressor to cook and eat the tutelary familiar. However, she keeps the creature’s bones and it is they who guide her to her destiny.

Writing on possessed fish being eaten in some cultures, Robert Graves in The Golden Bough discusses Indian rituals where such a fish is eaten as a fertility rite to reincarnate the spirit in a new child. The same ancient Greek word for fish and womb is delphos, suggesting ancient associations between fish and fertility; some speculate that this is the symbolism of the mermaid.

[4] Also possibly history’s first recorded foot fetish.

[5] There are no slippers in this version. Herodotus is discussing Greek hetaera, those superior female courtesan companions, educated and erudite, the only women whose presence was welcomed and well-regarded in the Greek symposia. Rhodopis is one of only two hetaera he names (the other is Archdyke).

If historical Rhodopis was indeed an hetaera then Charaxus must have paid a high purchase price indeed for it to be noted. Demosthenes records that the hetaera Neiara bought her freedom for 30 minas, perhaps $575,000 in today’s currency.

Sappho later wrote a poem accusing Rhodopis of conning her brother out of his property.

[6] The full quote, from Histories 2.134.1&2 (Loeb) is “Some Greeks say that it was built by Rhodopis, the courtesan, but they are wrong; indeed, it is clear to me that they say this without even knowing who Rhodopis was (otherwise, they would never have credited her with the building of a pyramid on which what I may call an uncountable sum of money was spent), or that Rhodopis flourished in the reign of Amasis, not of Mycerinus.”

Several historians attest that Rhodopis dedicated a great deal of treasure at the Oracle of Delphi however, which was on display for centuries thereafter.

[7] Cinderella: Three Hundred and Forty-Five

Variants of Cinderella, Catskin and, Cap o’Rushes, Abstracted and Tabulated

with a Discussion of Medieval Analogues and Notes, Marian Roalfe Cox, 1893.

[8] Pulp is a portmanteau team for a genre of

action-oriented character-rich plot-driven writing that provokes gut reactions

in its readers. It is typified by the cheap 1920s and 30s mass-marketed U.S.

magazines such as Weird Tales that popularised the term, but includes a

wide range of sources and is still a popular literary medium today. Horror,

romance, adventure, mystery, it’s all got to get the heart pumping and keep the

pages turning..

[9] Readers are directed to www.prose-press.com and to the volumes The New Adventures of Richard Knight and Blood-Price of the Missionary’s Gold: The New Adventures of Armless O’Neil.

[10]

“Kindle ebook sales have overtaken

Amazon print sales, says book seller”, The Guardian, 6th

August 2012

[11] This is perhaps contentious. There are all kinds of conflicting statistics out there for book sales, confused and confounded by commercial confidentiality and optimistic marketing. Perhaps the most robust US stats come from the Census bureau, which records year-on-year book sales income as follows: 2002= $15.45bn, 2003=£16.24bn, 2004=$16.88bn, 2005=$16.89bn, 2006=$16.99bn, 2007=$17.18bn, 2008=$16.87bn, 2009=$16.05bn, 1010=$15.66bn; 2011=$15.53bn.

Codex Group, which describes itself as “the leader in book audience research and pre-publication book testing”, released statistics through their website at http://www.codexgroup.net/ based upon a quarter of a million interviews since 2004. Their research suggests that within two years the percentage of purchasers who discovered new books in-store has dropped from 35% to 17%. In the same period, books bought because of personal recommendation rose from 14% to 22%, of which three-quarters were face-to-face recognition.

[12] This would be Russian Formalism, Viktor Borisovich Shklovsky’s 1930s work on understanding narrative.

[13] Morphology of the Folktale (1928, but not translated to English until 1958) by Vladimir Yakovlevich Propp analysed the basic plot components of Russian folk tales to identify their simplest irreducible narrative elements.

[14] Book of Genesis, Chapter 1, verse 3.

[15] Genesis 2: 19-20: And out of the ground the LORD God formed every beast of the field, and every fowl of the air; and brought them unto Adam to see what he would call them: and whatsoever Adam called every living creature, that was the name thereof. And Adam gave names to all cattle, and to the fowl of the air, and to every beast of the field…

[16] Exodus 20.7, the third of the Ten Commandments; also listed in Deuteronomy 4.11

[17] “And the whole earth was of one language, and of one

speech. And it came to pass, as they journeyed from the east, that they found a

plain in the land of Shinar; and they dwelt there. And they said one to

another, Go to, let us make brick, and burn them thoroughly. And they had brick

for stone, and slime had they for mortar. And they said, Go to, let us build us

a city and a tower, whose top may reach unto heaven; and let us make us a name,

lest we be scattered abroad upon the face of the whole earth.

And the Lord came down to see the

city and the tower, which the children of men builded. And the Lord said,

Behold, the people is one, and they have all one language; and this they begin

to do: and now nothing will be restrained from them, which they have imagined

to do. Go to, let us go down, and there confound their language, that they may

not understand one another’s speech.

So the Lord scattered them abroad

from thence upon the face of all the earth: and they left off to build the

city. Therefore is the name of it called Babel; because the Lord did

there confound the language of all the earth: and from thence did the Lord

scatter them abroad upon the face of all the earth.”

Book of Genesis XI:1-9, King James Version

[18] Many sources differ as to the dimensions and construction time of the Tower of Babel, but all agree that it was made from baked river mud-clay and mortared with bitumen (asphalt), the common construction technique of that part of the world at that time, and still sometimes used today. For example, the apocryphal Book of Jubilees 10:20-21 states, “And they began to build, and in the fourth week they made brick with fire, and the bricks served them for stone, and the clay with which they cemented them together was asphalt which comes out of the sea, and out of the fountains of water in the land of Shinar. And they built it: forty and three years were they building it; its breadth was 203 bricks, and the height [of a brick] was the third of one; its height amounted to 5433 cubits and 2 palms, and [the extent of one wall was] thirteen stades [and of the other thirty stades]” (Charles’ 1913 translation). This description suggests that the Tower was over one and a half miles tall. In 2010 the world’s tallest building was Burj Khalifa in Dubai, United Arab Emirates, at 2,722 feet a meagre half-mile high.

Genesis offers no dimensions but makes clear that the construction never met its intended height.

[19] J.F.D. Smythe’s A Tour of the Unites States of America (1784) records a Negro slave saying, “Kay, massa, you just leave me, me sit here,” from which some etymologists suggest a West African origin for okay in the Wolof and Bantu word waw-key or the Mandingo phrase o ke. Other scholars date the work back to the 1830s Boston comical misspellings abbreviation fad, citing O.K. as a shortening of “Oll Korrect”. Democrats claim it for its use in their “Vote for OK” 1840 presidential campaign for Martin Van Buren of “Old Kinderhook”, New York. This campaign also introduced the “O.K. sign” with the forefinger and thumb circled and the other fingers raised and curved – possibly the politest gesture originating in politics. It was fashionable until the 1960s to claim okay was a borrowed Chactaw word. Others believe the word a corruption of the Scots “Och aye,” the Lakota “hokahey”, Finnish “oikea”, German “ohne korrectur”, or the Greek “Ola Kala”.

[20] There are several variants of the name of the powerful Sumerian goddess of sexual love, fertility and warfare. The most prevalent is Inanna or Inana. Her Akkadian name was Ishtar. She shares many correlations with other love goddesses such as Aphrodite/Venus, including associations with the morning star, with doves, and with octangles.

[21] The same source that names Enheduanna also names her mother Tashlultum, who by the irreductable logic of biology was born first. Other early named women are Kubaba, a tavern keeper who rose to be the only queen to appear on the Sumerian King List (because she ruled in her own right, not through marriage to a king), and Peseshet, a fourth dynasty doctor and the earliest recorded woman of that profession except possibly the even earlier Merit-Ptah who held the title of “Lady Overseer of the Female Physicians”.

[22] Enlil’s origin myth story has been translated from a number of fragmentary tablets at the University of Pennsylvania, the Museum of the Ancient Orient in Istanbul, and the British Museum. Enlil ignores the laws of his homeland and seduces or rapes Ninlil, who bears him a child. When Enlil is banished to the underworld for his crime (which may have been ritual uncleanliness from pre-marital sex), Ninlil follows. Enlil disguises himself and when Ninlil asks him if he has seen Enlil he claims he has not – so she sleeps with the “stranger” instead. Three more children are successively conceived by this ruse, one of whom is the moon-goddess Nanna.

[23] Hogfather, by Terry Pratchett, Corgi, 1997, ISBN-10: 0552145424, ISBN-13: 978-0552145428

[24] Captain America #425, Marvel Comics, March 1994, written by Mark Gruenwald.

[25] The civilian identity of Captain America.